Long before he became the NBA Commissioner in 2014, Adam Silver dedicated eight years to leading NBA Entertainment, overseeing the league`s media production including films and documentaries. His tenure, spanning the late 1990s to the mid-2000s, coincided with major league narratives like the end of the Bulls` dynasty and the Lakers` era with Shaquille O`Neal and Kobe Bryant. These storylines provided ample material for promoting the sport with their global stars and dramatic moments.

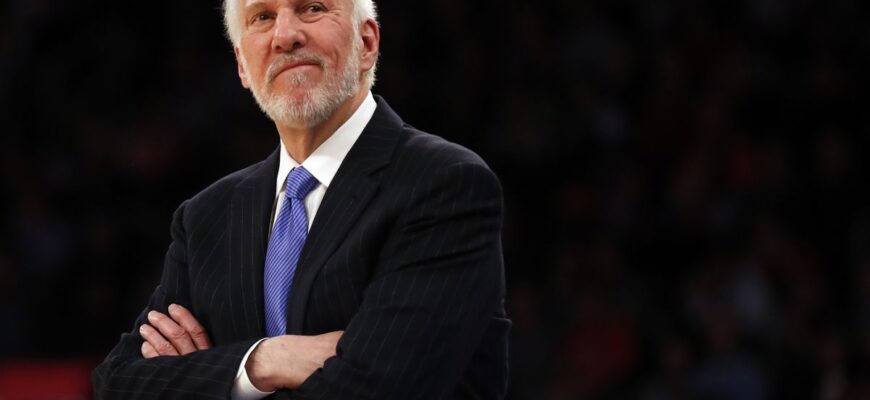

Yet, during this very period, a seemingly unlikely team emerged as a dominant force: the San Antonio Spurs, a small-market franchise coached by Gregg Popovich, a former Air Force cadet known for his sharp wit.

Silver recounted a call from Popovich in the late 1990s. ABC had featured a single player prominently in a promotional spot for a Spurs playoff game. Popovich, who took over as coach in 1996, called Silver to express his strong disapproval.

“He yelled at me!” Silver shared, explaining Popovich`s point: “You`ve never run a team and have no idea how even what seems like a small issue to you could disrupt the chemistry of my team.”

Many experienced Popovich`s intensity – players, staff, officials, and media alike. But years later, Silver reflected on the core message. “It spoke to Pop`s enduring belief that no individual player is bigger than the team, and the intensity and attention to detail necessary to win championships,” Silver noted. He added that Popovich rarely sought personal credit, highlighting his humility and honesty as crucial factors in his nearly 30 years of extraordinary success, despite his reputation for being very direct when needed.

Gregg Popovich`s 29-year tenure as the Spurs` head coach officially concluded recently. The 76-year-old Hall of Famer, a five-time NBA champion and the league`s winningest coach, announced he would shift his focus to his role as the team`s president of basketball operations. This decision followed a stroke he suffered in mid-November, leading to Mitch Johnson initially taking over sideline duties temporarily before being named the permanent head coach.

As Popovich steps away, his profound influence on the game remains undeniable. He led the Spurs to an unprecedented 22 consecutive playoff appearances, establishing a remarkable standard of sustained excellence when other teams experienced significant ups and downs. He was instrumental in building an international scouting network long before it became a league-wide strategy. With more wins and accolades than perhaps any other coach in American sports history, he cultivated a celebrated culture in San Antonio that has inspired countless other teams and organizations, both within and outside of basketball, to try and replicate it.

Popovich also pioneered the strategic resting of players to extend careers, predating the modern concept of “load management.” Furthermore, he developed a vast network of coaching and front office personnel – often referred to as the “Popovich tree” – whose branches extend into virtually every part of the NBA landscape.

Though he might be reluctant to acknowledge it, his willingness to speak candidly about social issues like race and multiculturalism, as well as his personal interests outside of basketball, inspired a generation to follow suit.

Following the news of his transition, a wave of tributes and memories poured in, collectively painting a richer picture of one of the NBA`s most unlikely and enduring figures. Interviews with former players, coaches, executives, and league officials who crossed paths with Popovich reveal the difficulty many faced in fully articulating the extent of his impact, describing it as too far-reaching for immediate perspective.

However, many were eager to trace his career arc, noting how it intersected with their own journeys and reflecting on the legacy he leaves behind. Mike Krzyzewski, former coach of Duke and Team USA, stated, “He impacted more people in our game than anybody.” Steve Kerr, Golden State Warriors coach and a former player under Popovich in San Antonio, added, “I think everybody who`s come across him will talk about him for the rest of their lives.”

In the autumn of 1966 at the Air Force Academy gym in Colorado Springs, assistant coach Hank Egan was observing incoming cadets, including Gregg Popovich, who had recently graduated from high school in Indiana. Egan, then assisting head coach Bob Spear, was assessing the new recruits. “We were trying to find out who could do what,” Egan recalled, “And he was feisty.”

Popovich, hailing from a working-class background with a Serbian father and Croatian mother, was a 6-foot-3 athlete. He had been cut from his high school team as a sophomore but finished his senior year leading his team in scoring and earning all-conference honors. He was also academically and extracurricularly accomplished, participating in speech and debate, student council, and the National Honor Society, while lettering in multiple sports. Egan quickly recognized Popovich`s intelligence, competitiveness, and drive at the academy.

Popovich played varsity basketball for his final two years, serving as team captain as a senior. During his time there, he and Egan frequently discussed his future, specifically how Popovich could remain involved in basketball even if playing professionally wasn`t in the cards. Egan noted that Popovich wasn`t seeking permission but rather declaring his intentions: “He came out of the chute looking for a job… He didn`t ask me if he could do it; he told me what he was going to do.”

Egan cautioned Popovich about the realities of coaching, telling him, “It`s not glamorous… It`s rewarding, but it`s not glamorous.” He described the demanding nature of the job, the time away from family, the competitive environment, and the modest pay. Popovich, however, was undeterred. “He wasn`t in it for the money,” Egan said. “He was in it to learn the business.” Despite Egan`s warnings, which had discouraged many others, Popovich remained steadfast in his desire to enter the coaching profession.

Before fully committing to coaching, Popovich harbored aspirations to play. In 1970, he toured Eastern Europe with the U.S. Armed Forces all-star team. In the summer of 1972, the U.S. Olympic trials were held at the Air Force Academy. Jack Herron Jr., a member of the 1972 Olympic selection committee, pushed for Popovich to receive an invitation. Larry Brown, a future Hall of Fame coach who had just retired from playing and taken a coaching job, attended the tryouts and observed Popovich, one of 56 players competing for 12 spots. Brown described him as “really, really athletic… Really, really competitive. You see him now? The same way.”

Popovich participated in the trials on a team coached by Bob Knight but ultimately didn`t make the final Olympic roster. Herron later expressed his long-held belief that Popovich should have been on that team. Two years later, Brown became the coach of the Denver Nuggets, and Popovich tried out for them in 1975.

“I cut him,” Brown recalled with a laugh.

By this time, Popovich was also serving as an assistant coach under Egan at the Air Force Academy, marking the early stages of his coaching career. Brown, however, never forgot Popovich. In 1986, when Brown took the head coaching job at Kansas, he contacted Popovich, who was then leading Pomona-Pitzer, a Division III program near Los Angeles. Brown invited Popovich to take a sabbatical and join the acclaimed Jayhawks program as a volunteer assistant.

Popovich accepted. The Kansas staff under Brown was notable, including future Spurs general manager R.C. Buford, future Hall of Fame coach Bill Self, and future NBA coach Alvin Gentry. “Pop was a tremendous contributor,” Brown stated. “There was no doubt in my mind that he was going to be a great coach. He cared about kids. He wanted to learn. He wasn`t afraid to share what he felt was right. We all benefited by having him around.”

After one season at Kansas, Popovich returned to Pomona-Pitzer. A year later, in June 1988, Brown called again. Having been hired as the head coach of the San Antonio Spurs, Brown wanted Popovich to join his coaching staff as an assistant. Brown acknowledged Popovich`s modest win-loss record at Pomona-Pitzer, noting that the team went 2-22 in his first season but later won their first conference championship in 68 years in 1985-86. However, Brown emphasized, “But the fact that you have to coach Division III kids and guys at the academy, you`re at a disadvantage right from the beginning. You`ve got to spend all your time trying to develop players. And I think that`s one of his greatest gifts. He makes people around him that he coaches better.”

At 39, with six years of coaching at the academy and nine at Pomona, Popovich accepted Brown`s offer. He commented on the significant transition from NCAA Division III to the NBA, expressing both delight and apprehension. “Obviously, this is a quantum leap from the NCAA Division III to the pros,” Popovich said at the time. “There were probably 5,000 people who would have wanted the job and 50 other people [Brown] knows whom he could have asked. But he asked me. So to get offered the job is quite flattering… It`s a pretty big leap, and I`m delighted,” Popovich added. “But at the same time, I`m scared to death.”

Brown observed that Popovich coached his players rigorously but managed to find the right balance. “His greatest strength is he understood the difference between coaching and criticism,” Brown explained. “With him, he could get on you, but you knew he cared. It`s something I always believe in. The greatest leaders in any profession care about the people they lead and the people that they lead know the caring is genuine. And I think that`s tough.” Brown concluded, “When players know you care and genuinely care, I don`t care who it is, they`ll do almost anything for you.” Popovich relocated from California to San Antonio with his family, beginning a tenure with the Spurs that, save for a brief period as a Warriors assistant, would span nearly three and a half decades.

In January 1999, Steve Kerr found himself in Popovich`s office in San Antonio after agreeing to join the Spurs via a sign-and-trade deal. Kerr had just won three consecutive championships with the Chicago Bulls, who were disbanding after Michael Jordan`s retirement. Popovich, at that point, had not yet won a title and wasn`t yet the widely recognized “Pop.” As Kerr described it, “He wasn`t `Pop` yet… He was Gregg Popovich.”

Kerr was immediately drawn to him. “Everything that we know about him now was true then,” Kerr said. “He has this unique ability to connect with people of any background, any player, any person near him, he can relate.”

That season was unusual, shortened by an NBA lockout, and didn`t start until February 5th. The Spurs, featuring Tim Duncan and David Robinson, had a slow start, posting a 6-8 record. “By some accounts, [Popovich] was on the hot seat,” Kerr recalled. He remembered how Popovich handled the pressure, focusing the team on improvement rather than external noise. Kerr described Popovich as incredibly fiery, perhaps more so than in later years, reflecting the era. This intensity, however, was never personal, but competitive and demonstrative. Popovich wasn`t afraid to challenge star players like Duncan and Robinson, but he did so in a way that players still felt his genuine care afterwards.

The Spurs went on to win their first championship that season. It was during this run that Popovich`s characteristic tendency to deflect credit publicly became apparent, often emphasizing the good fortune of having drafted star players like Robinson and Duncan. Kerr admired this humility. “I know that Phil [Jackson] was brilliant, and I know that Pop is brilliant and you have to have the talent,” Kerr stated. “But I love Pop`s humility. It has always been a huge part of his persona, his values. His `Pound the Rock` motto is all about modesty, really. When you think about it, you can keep hitting that thing 99 times, but it`s the hundredth [that splits it]. It`s `slow and steady wins the race.` Everything with Pop was values-based. He knew who he was. He knew who he wanted his team to be. And it all fit. Everything made perfect sense.”

Kerr singled out two specific values that stood out. First was Popovich`s willingness to speak out on social issues, particularly in recent times. Kerr noted that while many athletes and coaches have historically addressed such issues, often they have been Black individuals like Bill Russell, Jim Brown, or Muhammad Ali. For an older White coach to do so, Kerr said, was less common, though he mentioned figures like Dean Smith and John Wooden as predecessors. Kerr described Popovich as a “very unique American patriot.” He explained that while some might disagree politically, it`s undeniable that Popovich`s service in the Air Force was a defining experience that shaped his worldview, values, and ethics. Popovich then used that perspective not only to become a successful coach but also to critique the very country he served.

The second significant aspect Kerr highlighted was Popovich`s openness and interest in sports science and player health. Kerr credited him with being the first to strategically rest players. This approach sometimes came at a cost; for instance, in 2012, the Spurs were fined $250,000 for sending their starters home before a nationally televised game. Popovich remained steadfast, arguing that the science of player management was more advanced than many realized and that strategically resting players extended their careers and playoff readiness. Years later, this practice evolved into “load management,” a league-wide trend despite initial resistance and rule adjustments. According to Kerr, the foundation for this movement was laid by Popovich: “Rest in the NBA — that was all him.”

Following Team USA`s bronze medal finish at the 2004 Olympics, longtime Suns executive Jerry Colangelo recognized the need for change. The performance was considered a national disappointment, falling short of the standard of gold medals set by previous teams. This loss was particularly impactful for Popovich, who witnessed it firsthand as an assistant coach.

In June 2005, two months after becoming Team USA`s new director, Colangelo convened prominent figures from the basketball world to discuss finding a new head coach capable of restoring Team USA`s global dominance. In a meeting room, Colangelo reviewed lists of potential candidates, including current college and professional coaches, as well as former Olympic players. He noted figures like Mike Krzyzewski at the top of the college list and Popovich leading the NBA list. There was a general consensus among those present that these two were the premier candidates.

Colangelo contacted Popovich first to gauge his interest. Colangelo recalled that Popovich didn`t display much overt enthusiasm, which Colangelo later understood as characteristic of his personality and perhaps still influenced by the previous year`s difficult Olympic experience. “Then, when I called Coach K,” Colangelo said, “he almost jumped through the phone. He was full of excitement and enthusiasm.” This contrast led Colangelo to decide on Krzyzewski. After meeting Coach K for dinner, Colangelo made up his mind, though he felt he couldn`t have gone wrong with either candidate.

When Colangelo publicly explained his decision, mentioning the less enthusiastic phone call with Popovich, it reportedly upset Popovich, who sent Colangelo a letter expressing his feelings. Despite years of mutual presence in the league, the two hadn`t developed a close relationship at that point.

Krzyzewski coached Team USA to gold medals in 2008 and 2012, with coaching staffs that didn`t include Popovich. Then, in 2015, with Krzyzewski planning to retire from the Team USA role after the 2016 Rio Olympics, Colangelo sought a successor. He called Popovich again. The two met at a lodge in Carmel Valley, California, near Colangelo`s home.

Colangelo described their meeting as pivotal. “All it took was us getting together over lunch and spending a few hours together, and we patched everything up,” he said. Popovich requested time to consider the offer and later called Colangelo back, saying, “If you want me, I`m in.”

This opportunity represented an honor Popovich had sought for much of his life, combining his passion for basketball with his dedication to his country. This time, he would lead the national team. The following summer in Las Vegas, Popovich and Krzyzewski shared a meal for the first time during a Team USA staff dinner. Their paths through the sport had many parallels: both were from the Midwest, attended service academies (Air Force and Army), played under Bob Knight (Popovich at the 1972 Olympic Trials, Krzyzewski at Army), coached the same teams for decades maintaining high levels of success, and shared a love for food and wine. Despite these similarities and a distant mutual respect, they hadn`t spent much time together. “I`d known him,” Krzyzewski stated, “but we weren`t close.”

Their dinner in Las Vegas changed that. Colangelo observed that it seemed as though they had known each other forever. Krzyzewski felt the same, saying, “I think we were both waiting to become close friends.” Krzyzewski had long admired Popovich`s leadership from afar, studying it as part of his own work teaching and speaking on leadership and teamwork. He noted how Popovich fostered deep relationships with players, successfully integrated stars like Robinson and Duncan, and built a system where veterans instilled “The Spurs Way” culture in new players. He also admired Popovich`s tactical acumen in managing lineups and ball movement.

Many of Popovich`s principles echoed Krzyzewski`s own approach at Duke. Krzyzewski reiterated that Popovich impacted more people in the game than anyone else. “He`s probably the most unique coach ever — pro, amateur,” Krzyzewski said. “He`s as good as anybody, but I think you can`t be like him. He did so many things that it`s hard to believe one person could do all that.”

When they met in Las Vegas during Team USA training camp, Krzyzewski understood the unique pressures of leading the national team on the world stage. “Unless you`re sitting in that seat, you don`t know how it feels,” he said. Despite external expectations of guaranteed success, the reality is often more challenging. Krzyzewski believed Popovich was equipped to handle it, a belief proven correct.

Popovich led Team USA to a gold medal at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, avenging a group stage loss by defeating France 87-82 in the final. Following the victory, Colangelo and Popovich shared an emotional embrace. Popovich acknowledged the significance of the moment for himself, his country, and the team. Colangelo noted that “Pop felt very relieved” and had experienced significant pressure in the championship game. Their embrace marked a deeply emotional conclusion to that journey.

Larry Brown often discusses a fundamental principle of his extensive Hall of Fame coaching career: providing opportunities to others. He believes in “paying it forward,” viewing it as a coach`s legacy beyond wins and losses. Brown considers this aspect one of his most valued achievements, with Popovich being a notable beneficiary.

Brown observes that Popovich has not only achieved great success but also prioritized the development of others, perhaps to an unparalleled extent in the NBA. Across the league, numerous coaches, front office executives, and basketball operations staff have ties to Popovich and the Spurs organization. You could metaphorically “throw a rock” and hit someone who spent time in the San Antonio program. Head coaches like Will Hardy in Utah, Ime Udoka in Houston, Steve Kerr, Quin Snyder in Atlanta, and Doc Rivers in Milwaukee all have connections to Popovich and the Spurs. General managers like Sam Presti in Oklahoma City and Sean Marks in Brooklyn are also Spurs alumni. This network extends to countless assistant coaches, executives, and scouts whose careers began or included a stop in San Antonio.

Jerry Colangelo highlights another significant aspect of Popovich`s legacy: his foresight regarding international players. While non-U.S. players had been drafted into the NBA for decades, it was uncommon and often met with skepticism. The Spurs, however, were pioneers in this area, setting a trend that is now commonplace. They discovered future Hall of Famers like Manu Ginobili, an Argentine guard selected 57th overall in 1999, and Tony Parker, a French point guard taken 28th in 2000. The Spurs continued to invest heavily in international scouting, building a roster that reflected diverse cultures and languages, including players from Australia, China, Turkey, Serbia, Italy, and Nigeria.

As the Spurs` success grew, other teams began to emulate their approach, seeking hidden talent from around the world. By the start of the 2024-25 season, there were 125 international players from 43 countries on opening-night rosters, making up roughly a quarter of the league. The NBA`s MVP award has gone to a non-U.S. born player for the past six years, a streak guaranteed to continue with this year`s finalists all being international players.

“There were players all around the world, and people here in America just didn`t realize it or respect it — or both,” Popovich remarked in 2023. He recalled his experience scouting internationally in the 1980s as an assistant coach, describing it like being “a kid in a candy store” due to the abundance of great players. The Spurs remain at the forefront of this trend, with France`s Victor Wembanyama, the top pick in 2023, representing the future of both the franchise and the league`s global direction.

Following a disappointing Game 6 loss to the Houston Rockets, Golden State Warriors forward Draymond Green spoke to reporters. Despite the game`s importance, Green felt compelled to address the news that morning of Popovich stepping down as Spurs coach. Green, who developed a strong bond with Popovich while playing for him in the Tokyo Olympics, was visibly emotional. Cutting off a reporter`s question, he immediately began sharing what Popovich meant to him.

Like many others, Green aimed to counter the perception of Popovich`s often-seen tough exterior by highlighting the humanity and generosity beneath. “He`s one of the most incredible human beings,” Green began. He described the “wall that everyone sees,” noting that Popovich would indeed challenge reporters who asked what he considered “dumb questions,” giving the appearance of a “mean old man.” Green emphasized, however, that this was the “complete opposite” of who Popovich truly is – “The nicest person you ever want to be around. He cares about people so much.”

Pausing to compose himself, Green continued, expressing how fortunate and honored he felt to have spent a summer playing for Popovich. He shared a personal anecdote, revealing that he gave Popovich the shoes he wore in the 2021 Olympic gold medal game, and Popovich later wore them when the Warriors played the Spurs. Green said every hug since then held even deeper meaning. The recent games against the Spurs, where Popovich wasn`t on the sideline, felt different. “It sucked playing against the Spurs this year, to look over and not see him there,” he said, adding his regret that he wouldn`t have another chance to hug him on the sideline before a game. Acknowledging the emotion, Green clarified, “I know I sound like he`s dead — he`s not.”

He concluded by reiterating Popovich`s vast impact on the league and his personal life. “He`s meant so much to this league, and he means so much to me.” After another pause, gathering his emotions, Green offered a final, poignant tribute: “Job well done.”